If you've ever said to yourself "Damn, what I really want to hear right now is some avant-garde music constructed from the sounds of old arcade machines," (and, let's face it, who hasn't said that at some time in their life?) , then today's your lucky day.

If you've ever said to yourself "Damn, what I really want to hear right now is some avant-garde music constructed from the sounds of old arcade machines," (and, let's face it, who hasn't said that at some time in their life?) , then today's your lucky day.Most people know the Belgian composer Wim Mertens, if at all, for his soundtrack to the Peter Greenaway film Belly Of An Architect, starring Brian Dennehey and Chloe Webb (whatever happened to her, incidentally?). Besides his occasional forays into film soundtracks, though, he's also responsible for some 50 albums, both as a solo composer and as a member of the ensemble Soft Verdict, as well as being the author of one of the first academic publications about systems music. Entitled American Minimal Music, the book, published in 1980, was an in-depth look at modern classical music in the US from John Cage to Steve Reich via LaMonte Young and Terry Riley. The foreword was written by a then-largely-unknown Michael Nyman. A friend who met Nyman some12 years later was astonished, then, to hear Nyman refer to Mertens as a "poor man's Philip Glass". I think the fact that Mertens got the nod to score Belly... rather than Nyman, Greenaway's usual musical choice, may have contributed to the slur. Despite this, I think Mertens holds his own, especially on albums such as Educes Me.

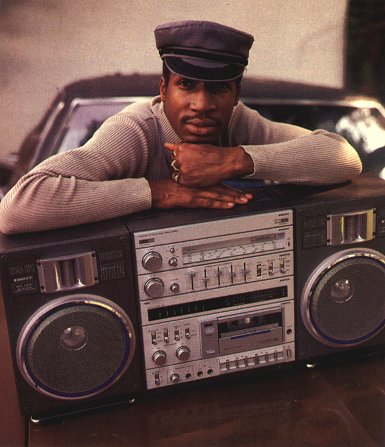

For Amusement Only, Mertens' first solo album, was made almost entirely from the sounds of pinballs and other arcade games; the sound sources are rather given away by the titles of each piece (e.g. Gorf, Fireball, Mystik). An acquired taste, perhaps, but the album found a niche audience among those who (a.) appreciated New York minimalism and (b.) misspent their youth in seaside amusement arcades. People like me in other words. Sadly, no other composers took up the gauntlet of creating music for, say, Frogger or Defender in subsequent years, though other musicians in other genres did use similar inspirations to Mertens in their work. These included Tilt's Arcade Funk and The Aphex Twin's early PacMan homage. In fact, PacMan has been the greatest inspiration for musicians over the years; the best example of which is arguably I'm The PacMan by the imaginatively monickered The PacMan. It appeared on the first Street Sounds Electro compilation, which has just been reissued on bootleg vinyl, so you've no excuse for not owning it.

Mertens' efforts, however, predate PacMan by a year or so, and two of the tracks from For Amusement Only are presented here for your edification. Enjoy, and wallow in nostalgia for the time when you nicked ten pence pieces from your mum's purse.

Download 8Ball

Download Invader ( both deleted Feb 2007--sorry!)